(PART I: A Brief History and Taiwan’s IC Tech Development from Successful Democratization and Liberalization)

Sasirada Sringam

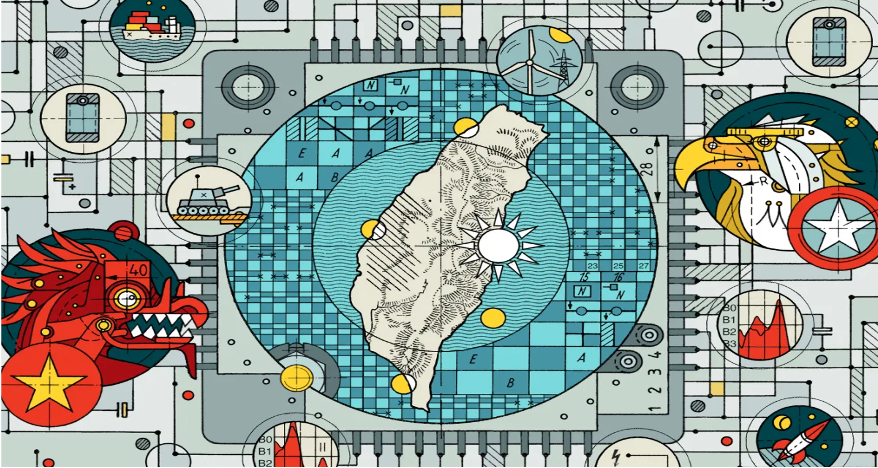

When discussing the world’s leading semiconductor companies, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) is universally recognized. TSMC always ranks as the top choice for productivity and investment in the semiconductor industry. With its increasing share prices and AI-related stocks, TSMC has benefited significantly from the growing demand for AI market and advanced innovative process technology, owing to its esteemed and high-quality chip production and development capabilities.[1] Consequently, Taiwan can eventually leverage its influence thanks to its “Silicon Shield”[2] characteristic, endowed by the worldwide semiconductor industry.[3] But what are the reasons behind this renowned label? This article argues that the Silicon Shield label, encapsulating Taiwan’s prowess, can be attributed to two main reasons. Firstly, Taiwan boasts the world’s premier semiconductor quality, advanced by robust public sector infrastructure, capabilities, financing, and investment funds dating back to the 1960s when high-technology manufacturing was first established within the public sector. These processes have been further developed through Taiwan’s successful gradual democratization and liberalization. Secondly, the current high global demand for semiconductors, driven by the ongoing U.S.-China geopolitical competition which spanned from the Trump administration and continues under Biden, further strengthens Taiwan being as a choke point position on the global stage for semiconductor demands.

This article would like to explore each rationale behind the creation of Taiwan’s Silicon Shield label and its skyrocket global dominance of semiconductor fabrication amidst U.S.-China technological and geopolitical competition into two parts. For the first part, this article will firstly trace back to Taiwan’s semiconductor development within the public sector by examining how Taiwan has cultivated its agencies and institutions from its gradual process of democratization and liberalization, which afterwards evolved semiconductor innovation and the evolution of its semiconductor technologies, especially within the Integrated Circuit (IC) technology. Subsequently, the second part will explain another rationale by exploring the contemporary global context of semiconductor demands, driven by the U.S.-China tech competition, and Taiwan’s strategic position as a chokepoint that complies with Taiwan’s foreign policy of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) during the administration of Tsai Ing-wen and the successor, Lai Ching-te.

Before Taiwan became the world’s best in semiconductor quality in this present, Taiwan had been constantly developing its procedures and technologies alongside its economic growth, which was accompanied by a gradual process of democratization and economic liberalization, until Taiwan settled semiconductor industry for its primary specialty. Taiwan had started its semiconductor industry around the 1960s, however, the industry became explicitly successful in the late 1990s, taking more than 20 years to progress, even though this was the shortest duration acceptable worldwide.[4] This is because during the period from the 1960s to the late 1990s, Taiwan relied on the public sector, including government entities, bureaucracies, and agencies, and faced with political transaction problems.[5] However, Taiwan can eventually establish democratization successfully which subsequently evolved policy development as well.[6] Taiwan was able to overcome this challenging factor by providing four solutions to improve fundamental policymaking, especially in the field of industrial policy for innovative computer science. Firstly, Taiwan provided finest education for technocrats and scientists in technological developments. Secondly, Taiwan provided several foreign advisors to enhance economic growth. Thirdly, Taiwan established institutional arrangements through Hsin-chu Science-based Industry Park to develop technologies (HSIP) and set up an autonomous organization called the Association of Allied Industries (AAI) to influence and support industrial development for technological science, particularly semiconductors. Lastly, Taiwan built joint ventures instead of wholly government-owned ventures, reconstituting developmental alliances through firm-level organizations and R&D (Research and Development), which eventually encouraging technocrats to set up their own semiconductor-related business and technological entrepreneurs.

Between the 1960s and 1980s, it was a period coinciding with the Cold War and Taiwan’s economic (miracle) development, mobilizing economy through the state-led process, as knowingly described as developmental state.[7] Most of Taiwan’s policies were initiated and nurtured by the government. Earlier on, initially as a partner of the United States before defeating in the Chinese civil war to the Communist Party in 1949, Taiwan must rely on Washington for conditions of geopolitical security and economic growth after retreating to conquer the island, as it be in this present.[8] Thus, at that time, Taiwan was being the constrain for countering communist expansion and strengthened its economic prosperity through Washington’s support. Therefore, the strategic geopolitical locations of East Asian states in the context of the Cold War also provided Taiwan to pursue mercantilist policies.[9] These had made Taiwan attract capital and technology from the U.S. Asian partner countries, like Japan and South Korea, and especially from America itself through California’s Silicon Valley technology.[10] Consequently, the Taiwanese government focused on industrial technologies, subsidized by Washington as well as some minor assistances of partners, such as communications, information, electronics, and markedly semiconductors.[11]

During this period, Taiwan has undergone the process of minor democratization and economic liberalization. For Taiwan’s public administration, Ching-kuo Chiang, who succeeded his father, Chiang Kai-shek – the founder of Republic of China (ROC), consolidated power of all. Ching-kuo Chiang’s faction became the most powerful in the late 1960s and 1970s.[12] Chiang Ching-kuo made Taiwan’s technological upgrading a top priority when the rest of the world still saw Taiwan as a source for cheap toys and sneakers.[13] Later, Taiwan started pursuing industrial productivity as the main advantage of the island afterwards. However, many politicians, particularly top leaders, and ministers, may lack this kind of specialized knowledge required. Therefore, it is essential for governments to offer comprehensive education in these fields. Technocrats must possess expertise and functional indispensability due to the complexity and uncertainty inherent in these technologies.[14] As a result, the government provided scholarships for them to study abroad to determine policy goals, establish contracts, and evaluate performance within each specified study to develop semiconductors in every domain.[15] In the essence of this, technocrats are not merely agents for delegation but may also play a significant role in decision-making processes, assisting principals in selecting technologies and setting objectives.[16] Therefore, the Council for Economic Planning and Development (CEPD), serving as Taiwan’s pilot agency since the 1960s, has persisted throughout this period from technocrats’ specialties, while the function of industrial policy making has been taken over by the Ministry of Economic Affairs (MOEA), with reinforcement by other government and government-supported organizations, such as the Ministry of Science and Technology (formerly the National Science Council), the Institute for Information Industry, and the Industrial Technology Research Institute (ITRI).[17] Together, these organizations pursue policy analysis in consultation with business confederations such as the National Association for SMEs, promoting technological development by undertaking industrial research, either on their own or with individual or consortia of business enterprises.[18] Until around the mid-1970s, the Taiwanese government established ITRI to advance technology industries and the Electronics Research and Service Organization (ERSO) to promote electronic industries for semiconductor developments.[19] Since then, ITRI and ERSO have been essentially centric in advancing semiconductor industry, enabling the 7-μm IC technology to cultivate ITRI and ERSO.[20] With helps of foreign advisors, provided by the government, Taiwan engaged several foreign advisors, including overseas Chinese and Americans, all of whom possessed extensive experience in the microelectronics field and had worked for leading electronic firms for many years.[21] These advisors were well-versed in technological and industry trends, as well as the time and costs associated with chip design and semiconductor projects.[22] For instance, two prominent IBM microelectronics division advisors, Bob Overton Evans and Wen-yuan Pan, held key positions in semiconductor development respectively as well.[23] However, Chiang still imagined that one day he would reclaim the mainland China back. To reclaim that as expected, Taiwan needs to have more power from the aspects of economy and military first.

Later, in the late 1980s, Taiwan faced a crisis as its long-time political leader, Chiang Ching-kuo, passed away in 1988. Before his death, there were important steps towards democracy with the founding of the oppositional Democratic Progress Party (DPP) in 1986 and the lifting of martial law by the Kuo Min Tang party (KMT) government in 1987.[24] From then on, the rivalry between the two political parties fundamentally changed “the state-society relationship.”[25] Moreover, Taiwan started changing identity as being “the pure Taiwanese” rather than being as “Chinese” people.[26] Consequently, Taiwan’s democratization has started elevating, turning political environment to be more liberal, or not being as a part of the mainland China.[27] As can be seen during the 1990s, President Lee Teng-hui introduced the explicit policy of “Don’t rush, be patient” (戒急用忍)[28] to discourage the expansion of cross-strait investments.[29] Investors who did not report their cross-strait investments to the government would be fined and some of them even received prison sentences.[30] In reaction, many Taiwanese investors, particularly those in high-tech industries, chose not to disclose their investments to the Taiwanese government.[31] Instead, they opted to register their investments in third countries such as the Cayman Islands to manage their ventures in China. Later, the DPP president, Chen Shui-bian, contended that the relationship between China and Taiwan could be best characterized as “one country on each side.”[32] Chen’s administration further revised the old high-school textbooks, replacing the historically China-centric narrative with a focus on Taiwan.[33] At this point, Taiwan has been democratized and liberalized gradually from the “China factor,” which is excluding itself from the mainland, shaping the imagined community as the Taiwanese nation in every aspect of governance, from language, memory, culture, and politics to naming Taiwan as a state, excluded from the mainland.

Accordingly, in the late 1980s, ITRI eventually initiated and promoted high value-adding wafer fabrication. Following during within the same year, when ERSO spun off Taiwan’s first mainstream IC company – United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC) – private businesses hesitated to engage in the semiconductor sector due to perceived high risk.[34] Despite government persuasion, only three private firms reluctantly became minority holders of UMC. Even after UMC’s success, local private investors were still hesitant to participate in TSMC formation due to their small size and risk aversion.[35] Therefore, MOEA resorted to threats of tax audits, halting permits, government contracts, and loans to support and secure necessary private investments for Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company Limited (TSMC) formation. Thus, both UMC and TSMC, Taiwan’s leading semiconductor companies, originated as spin-offs from the government agency, IRTI and ERSO.[36] During the 1990s, Taiwan established the Hsin-chu Science-based Industry Park (HSIP) to develop technologies, modeled after the successful Stanford Research Park in California’s Silicon Valley. Immediately after the establishment of HSIP, government leaders emphasized the creation of an autonomous organization called the Association of Allied Industries (AAI) in HSIP to function as a counterpart to the official Science Park Administration.[37] Also, the government supported these initiatives by encouraging technocrats to venture into entrepreneurship and providing technical and personnel support through ITRI and ERSO.[38] The rationale behind promoting startups or spin-offs from ERSO was that, in the 1980s, the private IC business was still in the nascent stages of the semiconductor value chain.[39] By advocating for startups and spin-offs from ITRI or ERSO, the government aimed to rapidly diffuse IC design and fabrication technology and knowledge from ERSO, enriching Taiwan’s local IC industry with resources from ITRI/ERSO. All semiconductor startups were founded by former ITRI/ERSO employees and graduates from the top three universities in Taiwan: National Taiwan University, National Chiaotung University, and National Tsinghua University.[40]

By the late 1990s, Taiwan’s IC technology reached the 1.0-μm level, but developed countries like the United States and Japan had already embarked on submicron technology development by the late 1980s.[41] Therefore, to maintain competitiveness, Taiwan needed to upgrade its technology. Thus, between 1990 and 1995, a total investment of NT $7 billion was earmarked for submicron technology development for leveraging Taiwan’s local manufacturers to get involved in the global DRAM/SRAM market that acquired the submicron technology necessary for mass production of DRAM’s and SRAM’s.[42] The project outline included developing submicron technology, establishing an 8-inch wafer submicron lab, advancing to 0.5-μm fabrication technology, and developing 4-Mb SRAM and 16-Mb DRAM designs.[43] Additionally, efforts of Taiwan were directed towards 0.35-μm technology modules and comprehensive micro pollution control techniques. Moreover, there was a focus on nurturing high-level technical expertise to meet semiconductor industry demands.[44] By 2003, HSIP boasted 370 firms with a combined output of $11.9 billion.[45] The semiconductor industry has consistently been one of the largest sectors within HSIP. Later, until nowadays, Taiwan has been manufacturing 63.8% of the world’s semiconductors, with its production of sub-7.0-μm high-end ICs commanding a global market share of more than 70%.[46] Taiwan’s IC packaging and testing output value also ranks first in the global semiconductor market, with a market share of 58.6%.[47] Furthermore, Taiwan’s IC design output value accounts for 20.1% of the global market, second only to that of the United States.[48] Therefore, according to world’s premier semiconductor quality, advanced by robust public sector infrastructure, capabilities, financing, and investment funds when high-technology manufacturing, Taiwan’s prestigious semiconductor’s quality was first established within the public sector. Over time, Taiwan has meticulously crafted institutional frameworks for technological advancement, particularly evident in its contributions to Silicon Valley like Industrial Technology Research Institution (ITRI). This has led Taiwan to eventually demonstrate its prowess through companies, enhanced by the advancement of IC technology.

[1] Paul R. La Monica, “TSMC Stock Rides AI Wave to $1 Trillion—or Is It $825 Billion?,” Barron’s, July, 08, 2024, accessed on 10th, July, 2024, https://www.barrons.com/articles/tsmc-stock-price-trillion-ai-744607b3

[2] The Economist Editors, “Taiwan’s Dominance of the Chip Industry Makes It More Important,” The Economist, March 6, 2023, accessed on 14th, April, 2024, https://www.economist.com/special-report/2023/03/06/taiwans-dominance-of-the-chip-industry-makes-it-more-important.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ouyang, Hongwu, “Agency problem, institutions, and technology policy: Explaining Taiwan’s semiconductor industry development,” Research Policy Volume 35, Issue no. 9 (2006), 1324, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2006.04.013

[6] Ibid.

[7] Hye-Ran Hwang and Jae-Yong Choung, “The Co-Evolution of Technology and Institutions in the Catch-up Process: The Case of the Semiconductor Industry in Korea and Taiwan,” The Journal of Development Studies 50, no. 9 (March 21, 2014): 1247-49, https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2014.895817.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] John A. Mathews, “A Silicon Valley of the East: Creating Taiwan’s Semiconductor Industry,” California Management Review 39, Summer, no. 4 (July 1997): 26-35, https://doi.org/10.2307/41165909.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Jinn Yuh Hsu, “State Transformation and the Evolution of Economic Nationalism in the East Asian Developmental State: The Taiwanese Semiconductor Industry as Case Study,” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 42, no. 2 (January 18, 2017): 171, https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12165.

[13] Gustav Ranis, “The Evolution of Policy in a Comparative Perspective: An Introductory Essay,” in The Evolution of Policy behind Taiwan’s Development Success, 1st ed., vol. 1 (New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, 1995), 1–26.

[14] Anurag Sharma, “Professional as Agent: Knowledge Asymmetry in Agency Exchange,” Academy of Management Review 22, no. 3 (July 1997): 758-60, https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1997.9708210725.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Pao-Long Chang and Chien-Tzu Tsai, “Evolution of Technology Development Strategies for Taiwan’s Semiconductor Industry: Formation of Research Consortia,” Industry and Innovation 7, no. 2 (December 2000): 185-90, https://doi.org/10.1080/713670256.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Chi-Tai Wang and Chui-Sheng Chiu, “Competitive Strategies for Taiwan’s Semiconductor Industry in a New World Economy,” Technology in Society 36 (February 2014): 60-73, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2013.12.002.

[22] Jinn-Yuh Hsu and Lu-Lin Cheng, “Revisiting Economic Development in Post-War Taiwan: The Dynamic Process of Geographical Industrialization,” Regional Studies 36, no. 8 (November 2002): 901-908, https://doi.org/10.1080/0034340022000012324.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Hsu, “State Transformation and the Evolution of Economic Nationalism in the East Asian Developmental State: The Taiwanese Semiconductor Industry as Case Study,” 168-170,

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Yin-wah Chu, “Democratization, globalization, and institutional adaptation: the developmental states of South Korea and Taiwan,” Review of International Political Economy, Volume 28, 2021, 1, 68-70, https://doi-org.chula.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/09692290.2019.1652671

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Hsu, “State Transformation and the Evolution of Economic Nationalism in the East Asian Developmental State: The Taiwanese Semiconductor Industry as Case Study,” 168-170.

[31] Ibid.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Wang and Chiu, “Competitive Strategies for Taiwan’s Semiconductor Industry in a New World Economy,” Technology in Society 36 (February 2014): 60-73

[35] Ibid.

[36] Chung Min Tsai, “The Nature and Trend of Taiwanese Investment in China (1991–2014): Business Orientation, Profit Seeking, and Depoliticization,” Taiwan and China: Fitful Embrace, October 3, 2017, 133–50, https://doi.org/10.1525/luminos.38.h.

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Yakov Amihud and Baruch Lev, “Risk Reduction as a Managerial Motive for Conglomerate Mergers,” The Bell Journal of Economics 12, no. 2 (March 1981): 605-10, https://doi.org/10.2307/3003575.

[40] Ibid., 611-613.

[41] Pao-Long Chang, Chintay Shih, and Chiung-Wen Hsu, “The Formation Process of Taiwan’s IC Industry—Method of Technology Transfer,” Technovation 14, no. 3 (April 1994): 161–71, https://doi.org/10.1016/0166-4972(94)90053-1.

[42] Ibid., 165.

[43] Ibid., 166.

[44] Ibid.

[45] Jian Hung Chen and Tain Sue Jan, “A Variety-Increasing View of the Development of the Semiconductor Industry in Taiwan,” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 72, no. 7 (September 2005): 850-65, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2004.06.002.

[46] Chen-Yuan Tung, “TAIWAN AND THE GLOBAL SEMICONDUCTOR SUPPLY CHAIN,” in Monthly Report, Taipei Representative Office in Singapore (November 2024): 4-5, accessed on 14th May, 2024, https://www.taiwanembassy.org/uploads/sites/86/2024/02/February-2024-Issue.pdf

[47] Ibid.

[48] Ibid.